Named Neurons

January 28, 2026

In our 2019 paper on augmenting neural networks with logic (Li & Srikumar, 2019), Tao Li, and I wrote about something called a named neuron. We introduced it as a concept that helped bind a symbol in first-order logic to an element of a neural network. Essentially, named neurons are symbols in neural networks. Over the years, I have found myself thinking about the idea often, and discussed them most recently in my neurosymbolic modeling class.

I am writing this note to elaborate on the idea. To get things started, we will look at what a representation is. Then we will look at symbols and neurons, focusing on how they both derive aspects of their meaning because of the computation they admit. Finally, we will see what all this has to do with named neurons.

What is a representation?

A representation is simply a mapping from one conceptual domain to another. In this relationship, one domain “stands in” for the other. Let us see some examples.

An ancient map. Images courtesy Wikipedia

A map is a representation of a territory. Every region in a map corresponds to some region in a territory. For example, consider this image of an ancient Neo-Babylonian stone tablet supposedly representing the world above.1 The stone tablet in the middle is an ancient map that does not follow modern conventions of map design. Wikipedia has a helpful diagram (shown left) that highlights the key information on the tablet. The diagram represents the tablet which in turn represents a territory (on the right). A map of a map, a representation of a representation!2

Sometimes a representation is built of names or symbols: elements of a (possibly

infinite) discrete set. Emojis are fantastic examples of symbolic

representations that convey prefabricated thoughts. For example, the symbol ⚠️

represents the idea of “warning” and ♀️represents the concept of “femininity” or

“womanhood”. Words and phrases like curiosity, transformer neural network

and Emmy Noether also refer to concepts that may be well-defined or vague.

Such names of concepts are useful because we can use them as prepackaged units

to talk to others. Moreover, such names also relate to one other. For example,

it is probably safe to say that the concepts of cat and dog are mutually

exclusive.

What do symbols mean?

Symbolic logic is a language of symbol compositions. There are many families of symbolic logic; let us take an informal look at first-order logic here.3 First-order logic has several different types of symbols, summarized in the table below.

| Constants | Refer to objects and concepts. They could be real or imaginary, and concrete or abstract | Salt Lake City, $\pi$, Emmy Noether, ⚠️, ♀️, curiosity, transformer neural network, Exit 213 |

| Predicates | State relationships between objects that could either be true or false |

IsHappy, IsTall, BrotherOf |

| Functions | Relate objects to each other | NextIntegerOf, RightEyeOf |

Using such symbols, we can write down claims like:

IsTall(John): “John is tall”, which may or may not hold.IsEven(4): “The number 4 is even”, which istrue.IsEven(NextIntegerOf(4)): “The integer that follows 4 is even”, which isfalse.

The language also includes the standard Boolean operators ($\wedge, \vee, \neg, \rightarrow, \leftrightarrow$) and the universal and existential quantifiers $\forall, \exists$ respectively. With these operators, we can compose statements like:

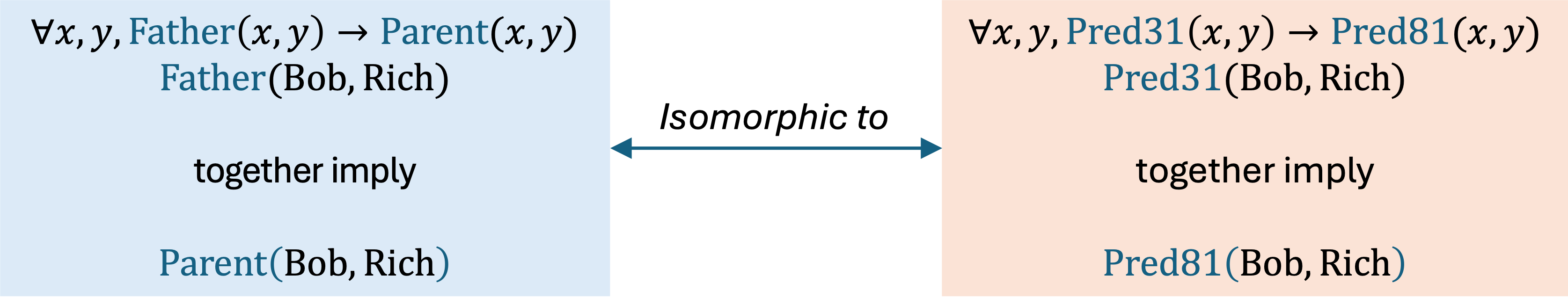

\[\forall x \in \mathbb{Z}, \texttt{IsEven(c)} \rightarrow \neg\texttt{IsEven(NextIntegerOf(x))}\]Using a rule like $\forall$ x, Father(x, y)$\to$ Parent(x,y) and the

observation Father(Bob, Rich), we can conclude that Parent(Bob, Rich). This

is an application of an inference rule.

But do the symbols by themselves have any meaning? That is, what do IsEven,

transformer neural networks and IsTall mean? They look like English phrases,

which is helpful for communication. But the machinery of inference does not

depend on the meaning and choice of the symbols. We could systematically rename

all the symbols and the computational steps of inference would not change.

For example, if we rename Father and Parent as Pred31and Pred81

respectively, but keep the names of the people as is, we would arrive at the

conclusion Pred81(Bob, Rich). This predicate is uninterpretable, and

practically anonymous. What we have done here is similar to renaming variables

in a program: refactoring correctly should not change the behavior of a program.

Renaming the predicate symbols produces a symbolic system that is isomorphic to the original one in terms of the computations that occur with them.

To a certain extent, this is a strength of symbolic reasoning. The process of inference does not need to know what the symbols mean. By merely manipulating symbols, we can arrive at valid conclusions without having any clue about what the symbols mean, or even if they mean anything at all. Systematic renaming of symbols will not change how they participate in computation, or what computation can be performed on them.

To summarize this part, there are two aspects to the meaning of a symbol:

- Meaning from name: What it intrinsically means according to conventional

understanding allows us to communicate symbols with each other. For example,

when I write

RightEyeOf, (I hope) I do not need to explain what that means. - Meaning from computation: What we can do with it, which does not depend on any intrinsic meaning of the symbols themselves. Symbols could be a private language if all we need to do is to perform operations on them.

Do neurons mean anything?

Modern neural networks, particularly transformer-type models, are essentially units of anonymous compute. They are vast computation graphs where internal nodes do not require intrinsic meaning to function. We can associate meaning with some elements of a network, usually at the edges. Let us look at two examples.

Suppose we use BERT to classify whether a sentence is imperative or interrogative. These labels have meanings defined by an external label ontology that is outside the model. The inner nodes of BERT, however, are “homeless” in terms of a semantic home. They are simply numbers in tensors that are influenced by data and not directly defined in terms of the linguistic concepts they help process.

Another example is the classic MNIST digit classification task. In a CNN trained on the task, the input is an image and the output consists of ten nodes, together the output of a softmax. Each output node is explicitly grounded to a digit from zero to nine. The outputs are clearly “named”. But what about all the activations in the layers between the inputs and the outputs?

There is, of course, work that shows that certain concepts can be discovered in neural networks. An early example is the “cat face neuron” in a trained convolutional neural network (Le et al., 2012). But these were accidents of training, and not the result of intentional design. That is, nobody designated a certain neuron to be the cat face neuron when the network architecture was designed. The designation was a post hoc imposition by an observer.

Sometimes, inner nodes are designated to bear meaning. A good example is the decomposable attention network (Parikh et al., 2016), an early neural network for textual entailment. Given a premise and a hypothesis, the network first encoded the words in both, aligned them using attention and used the alignment to generate a representation that led to the final entailment decision. The metaphor was that attention equals alignment. Nodes inside the network, trained end-to-end, represented soft versions of alignment.4

There are attempts to discover symbols inside neural networks by projecting them into high-dimensional spaces. Embeddings are distributed representations that pack multiple concepts into a single vector. Mechanistic interpretability techniques seek to disentangle these using tools like sparse autoencoders (Huben et al., 2024). To state this differently, mechanistic interpretability attempts to discover symbols or concepts inside neural networks.

What we have, one way or another, is a mapping from elements of neural networks (inputs, labels, inner nodes, or projections) to external concepts.

The interesting thing is that if you rearrange the matrices in the network, it is possible to reorganize the network so that the behavior does not change. But the internal structure is completely different. Nodes in computation graphs do not care about their specific “address” within the layer. That is, meaning is not bound to location but to computation. Swapping rows in a matrix produces a different matrix, but if subsequent computations account for that swap, the overall behavior remains unchanged.

So the lesson is that meaning in neural networks is bestowed in two ways: by tying elements to external concepts, and by the computational processes that operate on them. The meaning of a cat neuron is not intrinsic; it could have appeared elsewhere if the matrices were shuffled.

Once again, just like symbolic logic, meaning is a function of computation.

What are named neurons?

We have seen that both symbols and neurons acquire aspects of their meaning by the computation they admit. Symbols may have intrinsic (human-understandable) meaning by the choice of their name, and they are assigned meaning via mappings to external concepts. The name assigned to a symbol allows us to communicate about the system and constrain it. Can we similarly assign names to neurons?

In our 2019 paper, we said a named neuron is an element of a neural network that has external semantics. More precisely, it is a neuron that admits a mapping to a symbolic space.

Formally, a named neuron is a scalar activation in a neural network that admits a mapping to a symbol in a formal system, enabling logical reasoning over the network.

If a representation is a mapping from one domain to another, then a named neuron is a bridge that closes the gap between the discrete world of symbols and the continuous world consisting of tensors.

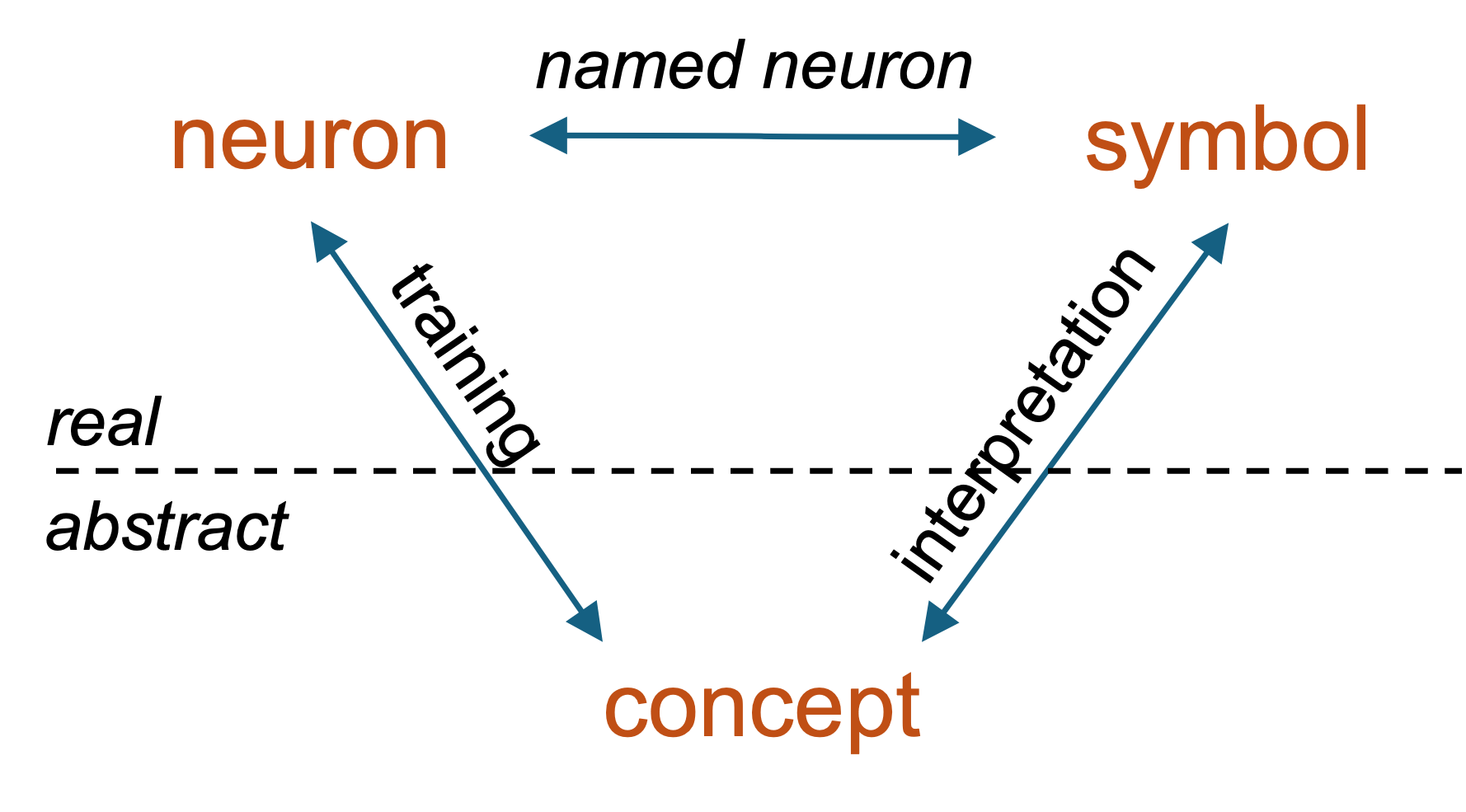

A three-way mapping of symbols, computation graph nodes and concepts

We can think of this as a three-way mapping. Symbols map to concepts through interpretations. Some nodes in neural networks map to concepts. We argue for a mapping between symbols and neural network nodes via named neurons.

In other words, while a neural network may be awash with anonymous units of compute, named neurons are some nodes in the network which may be recognizable as concepts.

Now we have a complete picture. Consider the BERT example again. The output node

labeled imperative is a symbol. In fact, it is a predicate. Outputs of neural

networks are predicates. Inputs are objects. This gives us a first-order logic

mapping. When a neural network predicts that a sentence x is an imperative, we

can think of it as asserting the truth of a proposition Imperative(x).

Inner nodes may also be predicates. For example, if the output node

corresponding to a cat label corresponds to the predicate IsCat(x) for an

input image x, then the “cat-face” neuron in the CNN might represent a

predicate called HasCatFace(x).

How do we find named neurons in practice? Sometimes they are designed in (output labels and even nodes in hidden layers, though not always), sometimes discovered post-hoc (cat face neurons), or extracted systematically through mechanistic interpretability techniques like sparse autoencoders. The field is moving from accidental discovery to principled extraction.

What does naming neuron give us?

Why bother naming neurons? Why not let the “distributed representation” handle everything in its high-dimensional, anonymous way?

Naming a neuron transforms it from a passive statistical artifact to an active participant in reasoning. Doing so opens the doors to new ways to think about neural networks.

First, we could write logical rules that constrain a network’s behavior despite what it learns during training. For example, we could have a rule that says “do not predict cat if a cat face is no recognizable”, written as:

\[\neg\texttt{HasCatFace(x)} \to \neg \texttt{IsCat(x)}\]We could enforce this rule at test time at the cost of extra compute for verification to get a more robust predictor.

Second, we could define loss functions that encourage rule-following behavior. This way, we would not need to apply the rule at test time. This approach promises ways for our models to do better than the data they are trained on.

Finally, named neurons could help enhance interpretability. Techniques like sparse autoencoders are essentially “naming machines”. They attempt to find latent symbols buried in the anonymous vectors by projecting them into a new space that disentangles concepts. We could even close the loop from interpretability to model improvement with constraints.

By naming a neuron, we give it a role in a larger story, one governed by the laws of logic, not just the randomness of gradient descent.

In future posts, we will explore how named neurons enable new training objectives and architectural choices. For now, the key insight is that by naming neurons, we gain leverage, namely the ability to reason about and constrain what neural networks do.

References

- Li, T., & Srikumar, V. (2019). Augmenting Neural Networks with First-order Logic. Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 292–302.

- Russell, S. J., & Norvig, P. (2021). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (Fourth Edition). Pearson.

- Le, Q. V., Ranzato, M. A., Monga, R., Devin, M., Chen, K., Corrado, G. S., Dean, J., & Ng, A. Y. (2012). Building high-level features using large scale unsupervised learning. Proceedings of the 29th International Coference on International Conference on Machine Learning, 507–514.

- Parikh, A., Täckström, O., Das, D., & Uszkoreit, J. (2016). A Decomposable Attention Model for Natural Language Inference. Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Huben, R., Cunningham, H., Smith, L. R., Ewart, A., & Sharkey, L. (2024). Sparse Autoencoders Find Highly Interpretable Features in Language Models. The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations.

How to cite this post

▼Recommended citation:

Srikumar, Vivek. “Named Neurons.” January 27, 2026. https://svivek.com/writing/named-neurons.html

BibTeX:

@misc{srikumar2026named,

author = {Srikumar, Vivek},

title = {Named Neurons},

howpublished = {\url{https://svivek.com/writing/named-neurons.html}},

year = {2026},

month = {January},

note = {Blog post}

}

-

If you want to nitpick, you might observe that even the rightmost image is a representation because it is just a map, not the actual territory. So what we have is a map of a map of a map. And if you want to nitpick more, you might note we have an image, i.e., a representation, of the stone tablet, not the tablet itself. ↩

-

If you are interested, Russell and Norvig’s AI book (Russell & Norvig, 2021) has an excellent introduction to logic that presents this more formally in the context of AI. ↩

-

Of course, not every use of the attention mechanism is interpretable. Self-attention within transformer networks are not. ↩